This article by Performing Medicine Associate Artist Liz Orton was first published by The Polyphony on 27 April 2021. Image credit Liz Orton.

What is the history of the represented body in healthcare? How does the way in which we look at the body shape what happens to it in clinical practice? How can photography be used to improve patient care?

These and other questions are behind a two-week Student Selected Component I teach every year, as part of the Performing Medicine programme, to medical students at Barts and the London School of Medicine. Alongside Treatment of Insistent Thrombosis, Immunoregulation and Tissue Regeneration and hundreds of other clinical options, students can choose Photography and Medicine. This is not a course in medical photography, but uses photography to open up a space between seeing and knowing, allowing medical students to develop critical, imaginative and personal responses to illness and its representations. Alongside many other courses delivered by artists for Performing Medicine, Photography and Medicine aims to expand and sometimes disturb biomedical modes of thinking about bodies.

Photography as a discipline emerged in close relationship with modern medicine[i] and provides a lens through which to reflect on the history of medical knowledge. From its outset, photography was understood as a mechanical medium, a detached form of observation capable of providing truthful accounts of the ill body. In the late nineteenth century it was used extensively to document, diagnose and monitor patients, and to disseminate learning among clinicians. The increasingly standardized usage of scale and composition helped establish photography as a consistent and reliable technology for recording and sharing patient cases. Photography became a natural ally of medicine, helping to secure the body as an object of clinical knowledge.

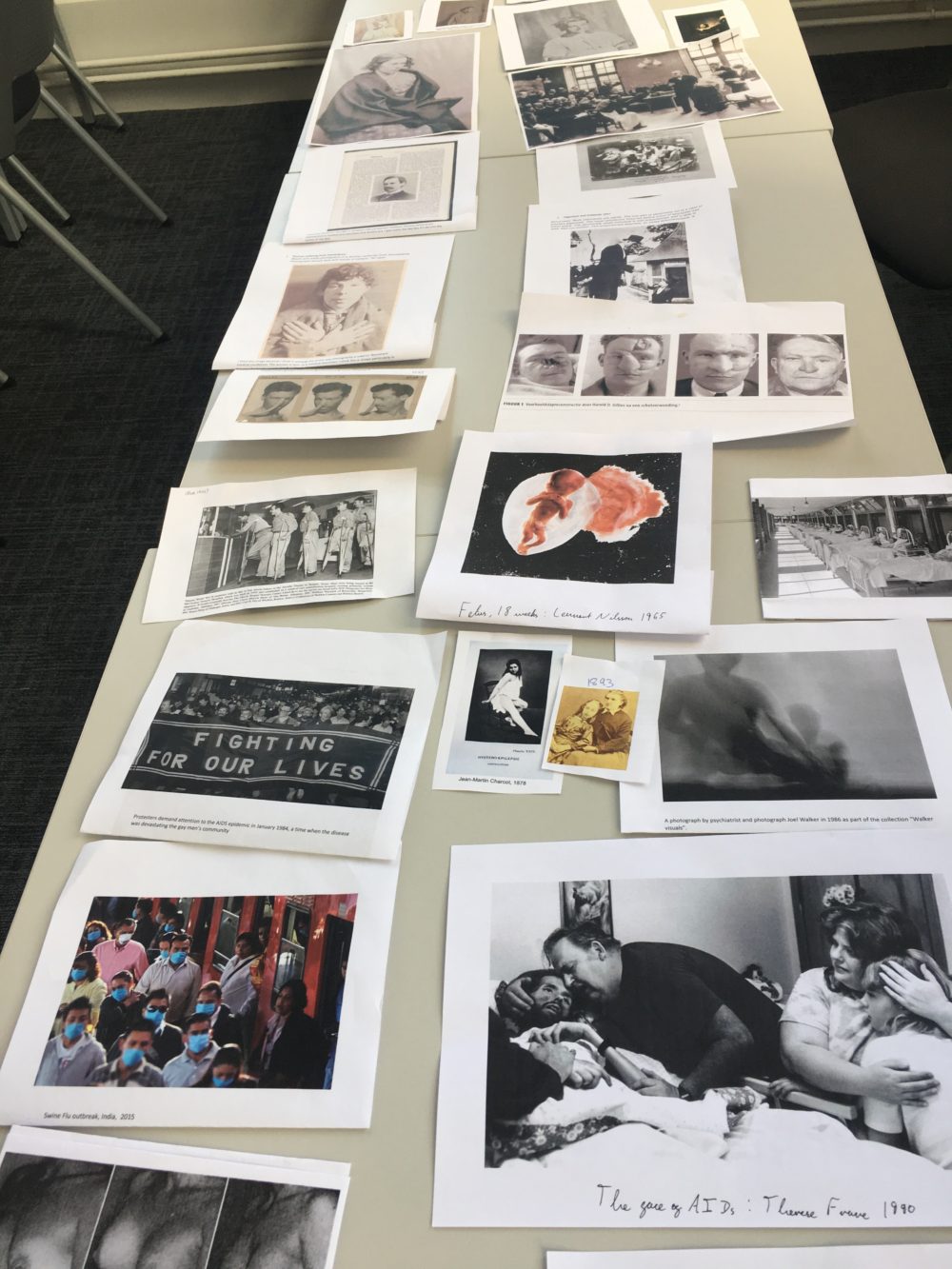

The medical school curriculum emphasizes contemporary knowledge; consequently, medical students tend to know little about their discipline’s pictorial past. I ask students to research and bring in photographs from medical archives, and we use these to assemble an improvised visual history. Creating a timeline of prints on the table generates exchange and discussion, and helps to identify recurring aesthetic concerns and motifs.

Image: Hugh Welch Diamond (1808-1886). Source: Wiki Commons, Attribution 4.0

It always becomes evident that this history reflects the interests and ideals of the photographers and institutions. Students can be surprised to discover, for example, that early images of ‘hysteria’ are all of young female patients, reflecting prevailing beliefs about the role of women’s reproductive system in mental health. As Georges Didi-Huberman notes, “Photography was in the ideal position to crystallise the link between the fantasy of hysteria and the fantasy of knowledge.”[ii] Many images of female asylum patients were staged (taking their references from literature, theatre and painting), inventing a highly gendered, class-based visual language for madness. Hugh Welch Diamond, a psychiatrist and photographer who worked at Brookwood Asylum in Surrey in the late eighteenth century, was one of a number of doctors who provided patients with dresses and props, photographing them against backdrops and scenery. These performative images then circulated as scientific ‘evidence’, helping to create and consolidate the idea of madness as a biological reality located deeply inside women’s bodies.

The history of photography tells numerous similar stories of discrimination and prejudice presented as disinterested evidence. Reviewing these histories is an important ethical endeavor for medical students, especially as so many early medical photographs persist as contemporary visual tropes. We consider some photographs of black patients with growths and skin diseases, taken in the 1890s, by the US surgeon Rudolf Matas. Matas attributed the high incidence of such diseases in black communities to biological inferiority, ignoring the role of social, political and economic inequalities in producing poorer health outcomes. This medicalization of inequality gave authority and legitimacy to racist views. Astonishingly, standard dermatology textbooks still routinely use white bodies as the only diagnostic reference. More hopefully, we are now able to look at a new medical textbook, Mind the Gap (2020), by medical student Malone Mukwende, that brings together images of dermatological symptoms in black and brown skinned patients.

Over time, of course, medical images do change. Via photographs of public surgeries, Victorian wards, military hospitals and TB treatment centres, we can trace shifts in medical norms and values. Current stock images of hospitals and patients, often used to illustrate patient leaflets and hospital websites, present quite conservative and highly sanitized images of care. Patients look relaxed, as if they are in a hotel rather than a hospital, resting rather than ill. Until recently the doctor tended to be male, not always but often white, and the nurses were invariably female. The doctor is active and absorbed, usually reading notes or observing the patient, and the nurses are cast in a supportive role, smiling for the camera and more likely to be pictured touching the patient. There is always only one patient, their body fully intact, and there is rarely blood, sweat or visible sign of illness.

***

Photographs frame the world, isolating what is important. Always open to interpretation, they are quick to produce dialogue and exchange. In my workshops, I encourage students to experiment widely with different genre: documentary, photo poetry, narratives, typologies, and montage. Photographic accidents are useful too as they destabilize the relationship between the world and its image. Students take tentative steps in sharing what would usually be considered extraneous or overly personal for the classroom.

Photo: Erica Lam

Medical students spend a large part of their education looking at representations of the body: drawings, illustrations, photographs, specimens, scans, models, data visualizations, medical dummies. Vision is the privileged sense, linking knowledge to seeing. But observation isn’t neutral, and it shapes the way illness is defined, affecting how it is lived. A large majority of medical students have heard of Foucault and are familiar with his idea of the clinical gaze as depersonalizing, focused on the pathology rather than the person. They are taught the importance of listening of their patient voices. But much of the curriculum still treats the body as a primarily biological mechanism that can be fixed by focusing on the parts that don’t work. Foucault’s critique of the clinical model is helpful as a way to make space for a social model of illness, and lets us consider the idea that a doctor’s approach affects how the patient feels, acts and recovers. Moving beyond Foucault’s framework, we contemplate the agency of patients, the materiality of the body, and significance of spaces of care to find more embodied ways to understand clinical relations.

Photographing illness

From the early 1970s onwards, visual artists began to use photography to produce counter-narratives of illness, pushing against medical categorization and foregrounding subjective experiences. Jo Spence, when diagnosed with breast cancer, used photography to resist the medical gaze, and represent her feelings of objectification and infantilization.[iii] During the first few decades of the AIDS crisis, numerous artists – including David Wojnarowicz, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Mark Morrisroe – took control of their illness experiences through photographic self-portraiture.

Social media has made the visual politics of illness more public and more uncertain. Sharing intimate photographs of illness can be therapeutic, allowing a renegotiation of identities, and becoming a way to connect with others [iv]. Photographs might be seen by thousands or even millions of people, part of a network of images shared and copied and circulated way beyond their original context. In this new and ever-expanding digital environment, photography offers new connections and communities, and has democratized narratives about illness and well-being. The flipside of this is a new form of illness: that we constantly fail to live up to the standards of the images we see. The self-image, more than ever a public image, is an increasing source of anxiety, offering both the promise of redemption and the threat of destruction.

***

Our position as observers is never neutral, and the act of looking is always ethical, political and social. Photography privileges the viewpoint of the observer over the observed and can be used to evaluate looking as an act of power. I give students experimental exercises in portraiture to do in pairs, varying their agency and decision-making powers. What is the experience of being represented by another? How do things change when the subject rather than the photographer directs the portrait? We reflect on the ethical space between photographer and subject to explore the importance of communication, listening and exchange. Photography as a metaphor for doctor-patient relationships is a way to explore trust and consent. As one student remarked, “I didn’t like being the subject, I didn’t have a voice or any control over the outcome”.

Photo: Ore Akinwale

We also consider the value of patient photography as a therapeutic tool that can help with recovery and rehabilitation. I share my own experience of facilitating photography projects with people with health-related issues: people with dementia; visually impaired communities; elders with mobility problems; young people with disabilities. The sense of agency and authorship that accompanies taking, editing and annotating photographs often helps participants to address the sense objectification and loss of control that can accompany critical or chronic illness. We use Deborah Padfield’s pioneering work in a London pain clinic as a case study: Padfield collaborates with patients to produce images that accurately express their experiences of pain, with the aim of using the images to improve clinical outcomes. For Padfield, the process allows a subjective experience to be objectified, and ‘a shared reference provided from which patient and doctor can work together to disentangle aspects of the pain depicted’.[v] These collaborative images give invisible pain a reality, and provide imaginative evidence that can aid patient/doctor understandings and lead to better informed programmes of care.

There is currently an increased interest in photography as a participatory method in health research, providing patients with an opportunity to participate in the generation of new knowledge. Photographs work differently from standard quantitative methods such as questionnaires and interviews. Photography can record and mediate the interpretation of patient experiences, and give patients an active role in the research process. Such approaches acknowledge that patients’ experiences are valid, and that patients can make valued contributions to research.

Photo: Vivienne Kit

There is a usually a lightbulb moment about half-way through the course when students understand that the aim is not to take good pictures but to use photography as a form of inquiry. At the end of the course students submit a portfolio and 2000 words of writing for assessment, and the grade contributes towards their degree, giving it equal validity with the clinical modules. Performing Medicine is to be thanked for this small but radical step. Students are encouraged to be exploratory rather conclusive, speculative rather than certain, and as personal as they want to be. This is a time when their own voices are given equal weight to those of any consultant or medical textbook. While many students start out on the course with a detached perspective they slowly allow themselves to become vulnerable, often making themselves or a family member the subject of their investigations. There have been projects about memory loss, kidney disease, depression, ethnicity and mental health, Crohns Disease, being a carer, cancer, Parkinsons, acne, eating disorders and many more.

Students often remark in the evaluation that they value the opportunity to participate actively in the learning process, enjoy the open dialogue with their peers, and start to see more obvious connections between their own lives and the curriculum. As one student wrote “I thought I was coming to learn about photography but really I have learnt about myself, relating to others, and being aware.” Once students make these connections they can relate differently, and art is no longer something outside science – an indulgent distraction – but a necessary and integral set of practices and ideas for becoming a good doctor.

*****

Liz Orton is a visual artist whose practice is concerned with language, authorship and the body. Her work engages widely with archives, both real and imagined, to explore the tensions between personal and scientific forms of knowledge. Liz is an Associate Lecturer of photography at the London College of Communication and is also an Associate Artist with Performing Medicine. Liz is the recipient of several major grants and awards including the MEAD Fellowship, a Wellcome Trust arts award and UCL Grand Challenges grant. Recent publications include Becoming Image: Medicine and the Algorithmic Gaze and Every Body is an Archive.

Notes:

[i] Amirault, C. ‘Posing the Subject of Early Medical Photography.’ Discourse , Winter 1993-94, Vol. 16, No. 2, A Special Issue on Expanded Photography (Winter 1993-94), pp. 51-76.

[ii] Didi-Huberman, G. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2004.

[iii] Spence, J. ‘The Picture of Health?’ in Putting Myself in the Picture: a Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography. London: Camden Press, 1988, 150-171.

[iv] On networked intimate images of illness see Tembeck, T. “Selfies of Ill Health: Online Autopathographic Photography and the Dramaturgy of the Everyday.” Social Media + Society, (January 2016).

[v] Padfield D. Perceptions of Pain. Dewi Lewis Publishing (2003)